My love for my work toys with me. I usually wake up a couple times a week in the middle of the night with some incredible idea about group leadership or communication, scribble it down on the pad of paper by my bed, then read it the next morning only to realize that my midnight assessment of incredible is way off.

But this is not about that. This is about one concept for facilitators and speakers that has stayed true with me over the past couple years. It's called The Infinite Ascent.

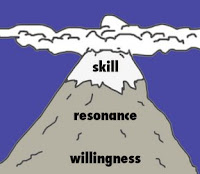

Basically, this is a model used to gauge a facilitator's primary success characteristics. The climb starts from the bottom, and it never ends (as shown by those lumpy clouds).

1. Am I willing to change? Specifically, am I willing to change my mental code of beliefs about what facilitation communication choices are best. It takes a lot of dismantling and rewiring to assemble a Primo Facilitator. If someone is not open to learning from experts or being coached by those who have more understanding and ability, then the person will not improve much.

2. How do people react to my communication (friends andstrangers)? Do people like to be around me? How much do I attract them? How often do I warm them up in conversation versus needing to be warmed up by them? How much do I get them smiling or laughing? At what rate do others get comfortable with me? What degree of positive impact do I make with people?

Resonance is the complex and layered ability of one's effectiveness to be with people - a constantly fluctuating dynamic based on who the people are and how they are feeling at the moment.

Unfortunately, I have seen group leaders have an angry emotional outburst in front of a group, get coaching on it, then dismiss the coaching because they don't understand the relevance managing one's own emotions has to being a group leader. Fortunately, resonance can be improved by learning from those who are better with it ("it" being charm, sense of humor or fun, quickness to engage, putting people at ease - basically any trait that 'works' with others), then trying what you observed for yourself.

A lot of people cry, "But I just need to be myself!" OK, but what if "yourself" is not effective? Chances are "yourself" is not an expert harpist, either. But just like learning to think and move one's body in new ways to play an instrument, learning to resonate with people in better ways is learned to the degree that one is willing to work for it (see #1).

3. Skill. Like a summit push, this is the most dangerous part of the climb. The biggest problem I see as people (rookies and veterans alike) learn about group communication is that they want to focus on 'skills' way too early and often, unconsciously ignoring the stability providing foundations of the climb - Willingness and Resonance. The funny thing about focusing on 'how my hands move', intricate linguistics ("you said 'like' seventeen times in four minutes"), where to stand, etc., is that the more you do it when you don't have a solid foundation, the worse you end up because there is not enough solid substance supporting the delicate intricacy.

Yes, facilitation skills are important. In fact, they are vital to understand in order to be a master communicator (here are some great ones, and here are some more by a great teacher). Yet they are trivial compared to one's willingness to learn and one's resonance with people. Focusing on skills without having deep willingness and wide resonance is like taking a helicopter to the summit of Everest and saying you climbed it. Um...no. You still have no idea what it takes to make the climb. Anyone can talk about hand movements and bean-count the number of times a person says "you know". But to be great, you have to make the entire climb, and that means sweat, strain, and pain.

One final point - remember the "infinite" part of the ascent. Just because you are really good and lots of people say so does not mean that you get to start using that helicopter. Exploring and improving upon one's willingness and resonance continues for the entire climb. And making strides gets harder as the altitude gets thinner.